Excerpt of Weaves of Power

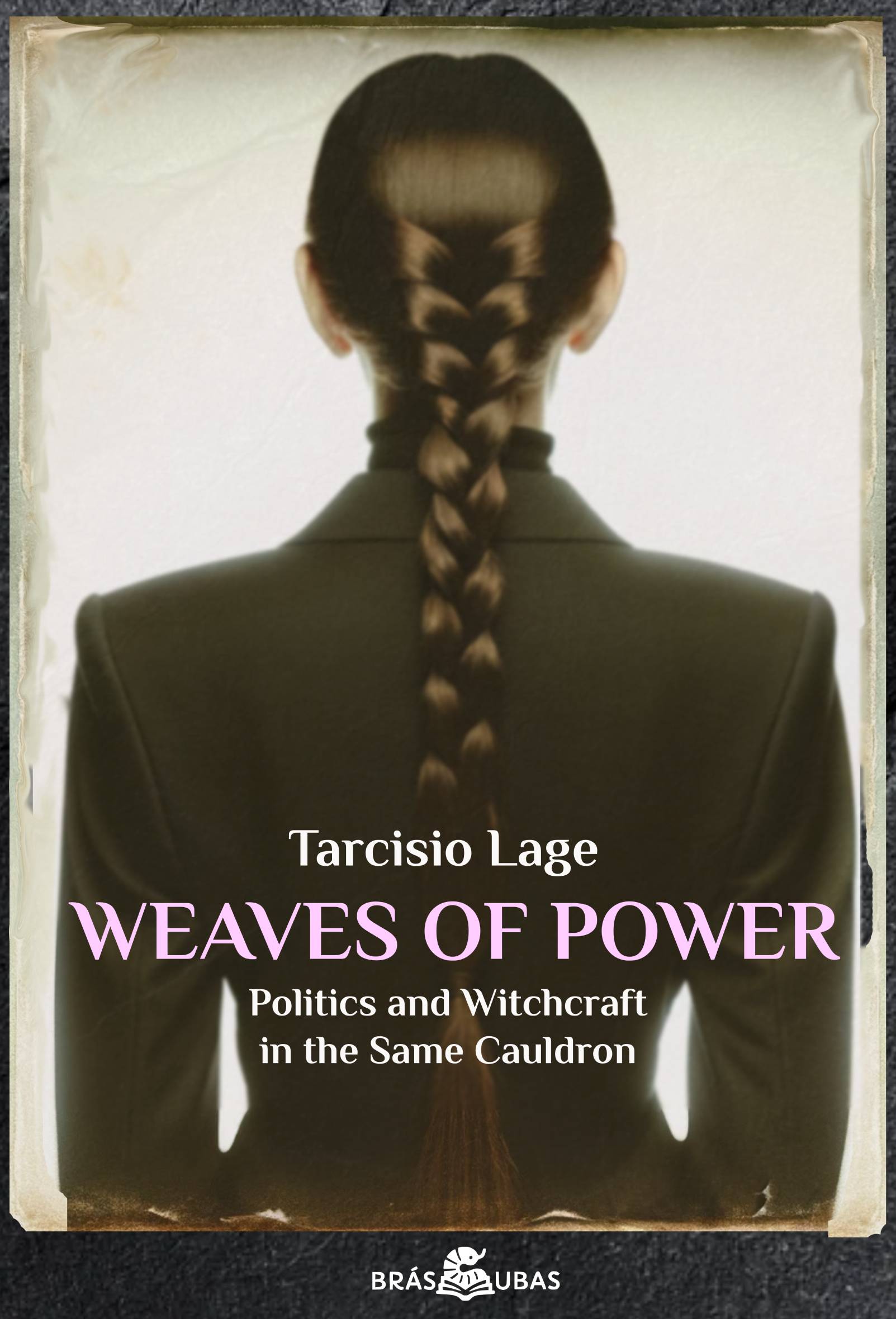

May 23, 2024Get to know the acerbic style of our newest translation in the Brazilian Contemporaries series, an enthralling tale that weaves political intrigue with witchcraft.

A brief overview of the events leading up to Tarquínio’s arrest for three cold-blooded murders.

It all started when he was still a young journalist in Rio de Janeiro and Tarquínio Esperidião decided to research the life of an aunt who had been murdered at the start of the second decade of the last century. She was shot in the chest with a 16-gauge shotgun, the shell ejecting intact like a cannonball. As it exited through the back, it made a huge bloody rose. The shooter—the brother of the victim’s stepfather—had been in love with and spurned by the girl. He had filled the cartridge not with lead, but with gold and silver pellets. His aunt’s name was Maria Amélia, but everyone knew her by the nickname Fiinha, given to her at birth by her mother. Indeed, it's not just a coincidence that the braided girl claiming to be Tarquínio’s daughter has the same name and the same nickname. Let’s take it one step at a time. Maria Amélia the First, or Fiinha the First, (let’s call her that to distinguish her from the second Maria Amélia, the focus of our tale) was, so to speak, the queen of Capim Alto, a prosperous farm in the interior of the state of Minas Gerais, near the city known as Santo Antônio das Tabocas. The stepfather, the servants on the farm, the regulars of the house, the brothers, and above all, the sisters, nurtured a mixture of admiration, respect, and fear for Fiinha the First. She commanded those around her with a gaze from her gray eyes, except perhaps her mother, Dona Adelaide, with whom she seemed to have sealed a pact during her pregnancy. This birth is worth a separate summary. Here is how it went down:

Adelaide’s first husband, Aristides, was a burly man with a dense beard and thick mustache, an authentic people breeder, very much in the mold of late-nineteenth-century landowners. The marriage, celebrated in 1888, had in fact been another pact, aimed at the merger of two large estates: Capim Alto, owned by Adelaide’s parents, and Ribeirão Fundo, owned by Aristides’ parents.

There was a problem, however. Adelaide, then fourteen, was not your typical maiden awaiting marriage, ready to spread her legs only when her husband told her so and with the primary intention of bearing his heirs. She was a rebel. She rode horses astride, like a Calamity Jane of the Cerrado Mineiro, not caring about the warnings that this could rupture her hymen. If she followed any commandments at all, none dictated “thou shalt always and in all things obey thy husband.” She had embodied the spirit of the suffragettes a few decades in advance. The spirit that would do so much damage to the sacred right of domination of husbands, fathers, and brothers.

Already on her wedding night, Adelaide’s disdain for her arrogant groom morphed into hatred at the sight of his disgusted expression when she mentioned a potential hindrance to carnal consummation. She was menstruating. In the teenager’s mind, there should be no problem if he wanted to proceed. If blood was to be spilled, it was already there, warm and perhaps even serving as a lubricant. But for Aristides, Adelaide was unclean and untouchable, as the Holy Bible decreed. The situation worsened the next morning when Adelaide’s prying mother-in-law rummaged through bedroom drawers and cabinets looking for a whip that Adelaide had owned since she was a girl. She liked to mingle with the farm hands, especially when it was time to separate the cows from the calves. Adelaide asked what she was looking for and only got an answer when her mother-in-law finished her search and found it. Then, emphasizing each word, she declared:

“In this house, only men go to the corral and use a whip. Women stay indoors, as they have plenty to do.”

Adelaide began softly muttering “Son of a bitch!”—she loved swearing—until it erupted loudly and clearly. The mother-in-law, Maria Aparecida Ferreira de Andrade, half-deaf, only heard the last part, like an explosion: “bitch!” She paused, surprised for a few seconds. Then she let go a high-pitched crackling scream capable of waking the entire farm. And that wasn’t it. She walked over and slapped her daughter-in-law in the face. The fury whirling around the teenager’s head indicated immediate retribution, but instead, she jumped up and ran off in her wedding nightgown. Her husband dragged her back by her hair through the cow shit. That night, she dreamt of her husband’s death. Many years later, now married for the second time, Adelaide would never tire in answering her companion in the card game Truco, Francisquinho, when he asked about her honeymoon:

“What honeymoon? I had a shitmoon!”

This explanatory note on the pact between Adelaide and Fiinha the First might be getting too lengthy, but the episode of the first night is essential for the reader to have an idea of what life was like for the couple and how this influenced the existence of this story’s central character. Aristides and Adelaide had four children: Aristides Filho, Orlando Andrade, Sebastião Andrade, and the youngest, Maria Amélia Andrade.

The last pregnancy, Fiinha the First’s gestation, was unlike any other—extraordinary in every way. For starters, Adelaide noticed a mysterious quality in her belly, something more rounded, almost luminous. Rather than kicking, the fetus seemed to gently caress her uterus, as if affirming Adelaide’s belief that she was carrying a girl. The pregnant woman adopted an unusual practice for the dawn of the twentieth century: she would lock herself in her room, get completely naked, and spend hours massaging her belly with almond oil. And so it happened that, one day when she had forgotten to lock the door, her husband burst in and saw her fully naked and caressing her belly for the first time, something he had not imagined seeing even in a brothel. His reaction was to strike with his whip, leaving a purplish bruise encircling Adelaide’s belly. This was also the first time she felt a sudden movement and a sense that the fetus had felt the pain of the whip and was crying out for vengeance, a call for vengeance mirrored in her tears of pain and hatred.

What happened next, on the afternoon of the same day as the flogging, could well be more than mere coincidence and not align entirely with the laws of probability. The foreman recounted the story, his eyes wide with disbelief. Everything coincided, to the smallest detail, with the dream Adelaide had had the day after the wedding, after being dragged like a rag doll through the corral’s manure.

Aristides’ horse had stumbled in an armadillo hole, throwing him off about fifteen feet. He landed on his head, broke his neck, and died in the arms of the foreman who tried to rescue him. Extra detail: during the fall, Aristides flung his right arm upward, causing the whip to lash out. It returned like a boomerang, coiling around his muscular belly, leaving a purple bruise that would only disappear with the corpse’s decomposition.

In his autobiographical book, Tarquínio goes into the fine details of the research on the life of Fiinha the First and recreates an image that was revealed to him by the witch herself:

Adelaide listened quietly and impassively to the report of the foreman, who was still visibly frightened. When women flocked to console her, she begged her pardon, saying that she would like to be alone, went into her room, undressed, oiled up her hands, and began massaging her belly. The soon-to-be-born girl adjusted her head to better feel the caresses, seemingly eager to share in the contentment visible in her mother’s eyes.

Up until her murder at age twenty-one, and even posthumously as Tarquínio’s research uncovered, Fiinha the First shared a bond with her mother that went a little beyond the affection of mothers and daughters. Severe and ruthless to the rest of her offspring, Adelaide never even scolded Maria Amélia the First, who did everything she pleased, dominating everyone with her gaze, two beacons that issued orders that could not be disregarded. Celma and Sena, two of Fiinha the First’s sisters, struggled to conceal their envy toward her, a sentiment that cost them dearly. Tarquínio details all the strange events surrounding the young witch until Juca Trindade, brother of Fiinha the First’s stepfather Amadeu, driven mad by unrequited love, shot her in the chest and killed her.

In his research, Tarquínio clashed with Rosa, Juca Trindade’s niece, who was examining her uncle’s life for a thesis at the University of São Paulo. Impelled by the witch—then dead for almost eighty years—Tarquínio ended up murdering Juca’s niece, in addition to destroying everything she had written about him. For Fiinha the First, Rosa was rehabilitating the memory of her killer, and this was inadmissible. Tarquínio transformed from a researcher into Fiinha the First’s puppet, murdering Rosa and then eliminating the victim’s maid and the building’s doorman to cover his tracks. The case became known as the Jardim Paulista Massacre or the Carnage on Marechal Castelo Branco Street. Tarquínio’s mind lost all links with sanity and, before being sentenced, he was hospitalized in the Jacarepaguá nursing home, where he came into contact with Dr. Anunciação and Sister Patrícia, one of the nurses at the clinic. When he was leaving the Jacarepaguá nursing home, and before a nosy reporter discovered that he was the monster of the Jardim Paulista Massacre, Tarquínio enjoyed a night of passion with Patrícia, leading to the birth of the new Maria Amélia, or the new Fiinha. In his autobiography, Tarquínio states unabashedly that he wasn’t the one who had sexual relations with Patrícia. It was Fiinha the First herself who had taken possession of his body with the confessed purpose of being reborn. In his autobiography’s epilogue, Tarquínio describes the first prison visit from Sister Patrícia and their seven-year-old daughter. She told that the name Maria Amélia came to her in a dream, suggested by a beautiful woman with braided hair and gray eyes, much like their daughter’s. Tarquínio lost all control when Sister Patrícia finally asked him:

“Don’t you think our Fiinha is beautiful?”

He pounced on the guard like a cat, wrested the rifle from his hands, and fired at the girl. Sister Patrícia flew like only a mother can, making her chest into a shield as she thrust the girl into the accompanying guard’s arms. As it exited through the back, the bullet formed a bloody rose, identical to the one on the back of Fiinha the First, eighty years earlier. Tarquínio was hauled out of the visiting room, nearly unconscious from the beating he endured. His autobiography ends like this:

“Yet, despite my dizziness, I couldn’t escape the scornful look the girl gave me as she was carried away in a policewoman’s arms.”